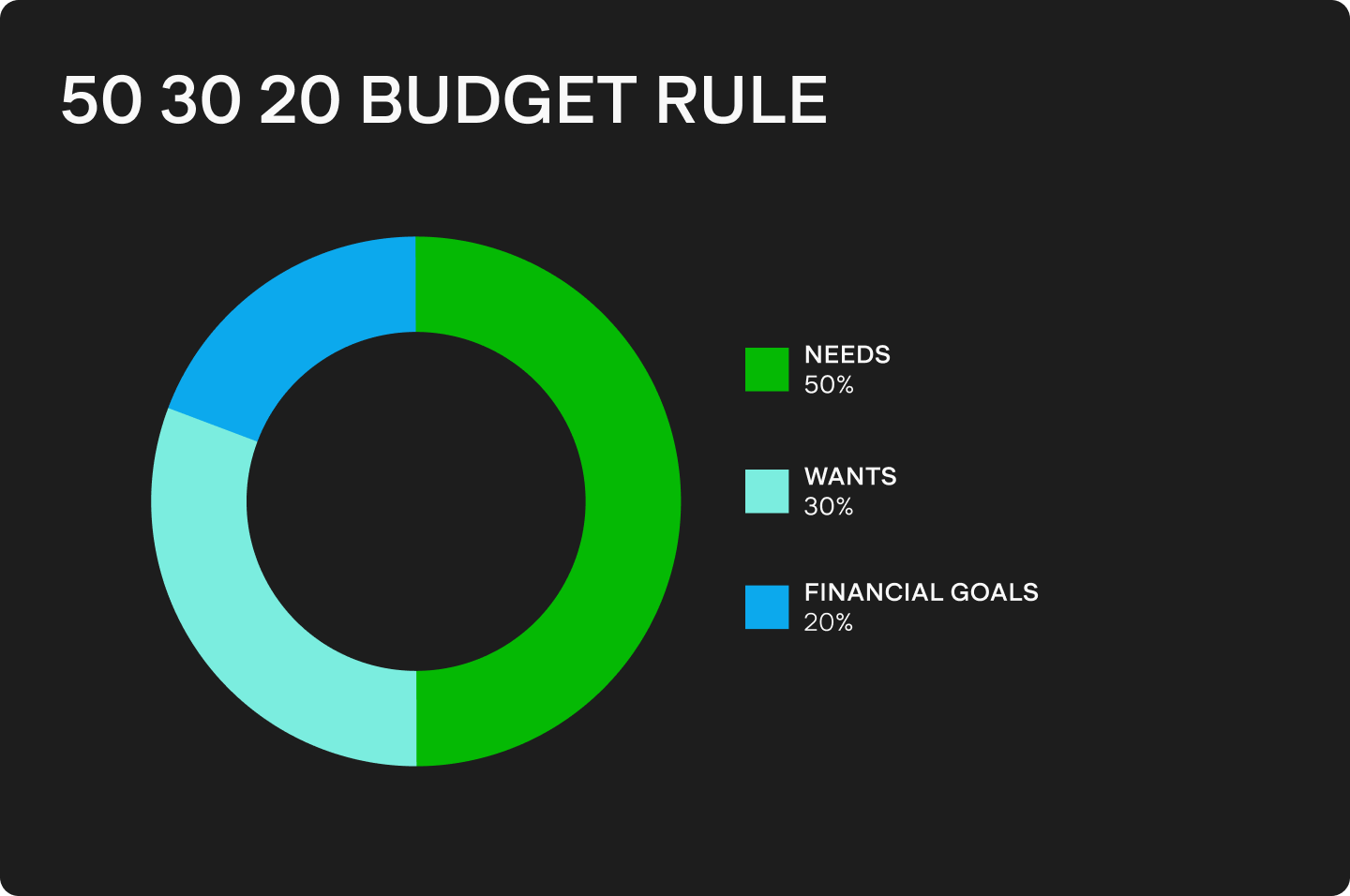

50 30 20 Budget rule explained

The 50 30 20 rule is a classic budgeting rule that can be applied no matter your income level. Read on to learn what the 50 30 20 plan is, how to implement it, and some common pitfalls to watch out for.

What is the 50 30 20 rule?

The 50 30 20 plan is a popular rule for effective saving and budgeting. Not only can the 50 30 20 budget rule be applied to any level of income, but it’s also incredibly straightforward to implement.

Here are the basics:

50%

Spend 50% of your after-tax income on needs. Needs are the expenses that would cause a significant lifestyle disruption if you didn’t pay them. Things like groceries, rent, and transportation costs fall under this category.

30%

Spend 30% of your after-tax income on wants. As the name suggests, wants are those expenses that are nice to have, but not essential. Think of expenses like takeaway, spa days, and streaming services subscriptions.

20%

Spend the remaining 20% of your income on financial goals. This is a broad category that includes goals like debt repayment, retirement planning, investing in stocks and ETFs, and saving for life milestones, such as buying your first property or a wedding.

To understand the finer points of the 50 30 20 rule of budgeting, let’s explore each category in more detail.

The 50 30 20 rule breakdown

50% on needs

On paper, spending 50% of your net income on needs sounds simple. In practice, however, it can be difficult to figure out which expenses are truly necessary.

For instance, you might think that your gym membership qualifies as a need since you need it to stay healthy. A critic could argue that you could forgo your membership and be just as healthy working out at home.

Needs vary between people. Someone passionate about their health and environmental impact may consider it necessary to pay a premium for organic produce at the grocery store. Others may consider that a nonessential luxury.

With that said, some expenses are considered needs for just about everyone. Here are a few common examples:

- Housing, like rent or mortgage payments.

- Insurance and health care.

- Transportation costs like gas or public transport fees.

- Utilities like heating/gas and internet.

- Minimum loan payments to avoid defaulting on debt.

Ultimately, whether something is truly a need is up to the individual. If not paying a certain expense would cause a significant and unpleasant lifestyle disruption, it’s safe to say it falls in this category.

30% on wants

Wants are your category for discretionary spending. These are all things you could certainly live without, but definitely make your life more enjoyable.

A few common categories of wants include:

- Clothing beyond basic needs, including accessories like watches and jewellery.

- Tickets to entertainment events, like movies, sports games, or gigs.

- Nights out at restaurants or bars, and ordering takeaway.

- Streaming services, video games, tech gadgets.

- Non-essential gifts for friends and family.

- Hobbies, like sports equipment and fees, gym subscription etc.

When it comes to adjusting the 50 30 20 plan to your own financial goals, the wants category offers the most flexibility. Since none of these expenses are necessary by definition, you can sacrifice some discretionary spending to achieve objectives like dollar cost averaging into your core ETF or building up a travel budget.

In reality, many individuals end up exceeding this 30% rule of thumb. Recent data indicates that Australian households spend about 37% of their total expenditure on discretionary items, meaning they are above the guideline recommended by the 50 30 20 budget rule.[1]

20% on financial goals

Finally, the 50 30 20 rule dictates that the remaining 20% of your income should be spent on financial goals. Common financial goals in this category include:

- Short-term goals like paying down debt. While minimum debt payments are necessary to avoid default and are typically budgeted under needs, additional payments can help you pay off your loans faster.

- Medium-term goals like building an emergency fund. Experts typically recommend an emergency fund with 3 to 6 months worth of living expenses. These funds can be held in different potential vehicles, including high-yield savings accounts or a short-duration bond fund.

- Long-term goals like saving for retirement. This can include both voluntary super contributions or investing in assets like stocks and ETFs using an investing platform.

Although saving for financial goals is the smallest category in the 50 30 20 plan, it is arguably the most important for long-term financial health. Unfortunately, many Australians are falling far below this 20% guideline. As of September 2024, Australian households had an average savings to income ratio of just 3.2%.[2]

🎓 Learn more: Guide on how to buy shares in Australia?→

50 30 20 budget example

To understand how to deploy the 50 30 20 budget in practice, we can take a look at a practical example. Consider Charlotte, a young professional earning a total post-tax monthly income of $5,000.

Based on the guidelines, Charlotte’s monthly spending in each category should be:

- $2,500 on needs

- $1,500 on wants

- $1,000 on financial goals

Suppose that Charlotte rents a room in an apartment with roommates and her housing costs come out to $1,700 per month.

After spending about $300 on groceries throughout the month, Charlotte is left with $500 to cover other essential expenses.

In terms of wants, Charlotte is able to spend $1,500 per month on discretionary expenses according to the 50 30 20 plan. However, since Charlotte is trying to save up for a deposit on a house, she chooses to take $300 of this amount and shift it towards her financial goals category, bringing the monthly total to $1,300 (with $1,200 remaining for her wants).

Charlotte splits between a mix of instruments including long-term investments in stocks and short-term savings in cash ETFs.

As this example demonstrates, the 50 30 20 plan can be a useful guideline to establish your practical financial plan, but adjusting it to your personal circumstances is key.

Calculate your own budget with this 50 30 20 calculator

To calculate your own budget according to the 50 30 20 plan, you can use this easy online 50 30 20 rule calculator.

As most Australians are paid fortnightly, double your regular take-home pay to find your after-tax monthly income. If you’re a freelancer or have another form of variable income, calculate your average after-tax earnings to come up with a prospective budget.

What are the benefits of the 50 30 20 budget rule?

Budgeting in some form is essential to building long-term wealth.

Without a budget, it’s easy to let short-term urges control your spending decisions without considering future savings. While the 50 30 20 budget rule isn’t perfect for everyone, it offers a simple and reasonable way to approach budgeting that can be applied across incomes, ages, and goals.

In addition to this rule’s simplicity and ease of use, it’s also realistic for many people’s situations. Rather than being overly strict and denying any discretionary spending, the 50 30 20 rule plans for wants, which can make you feel less guilty about spending on things you enjoy.

Finally, saving 20% of your pay aligns with many expert recommendations for financial health.

Should I create my own percentages of the 50 30 20 rule?

As we saw in our example, the 50 30 20 rule is designed to be flexible. That means adjusting the percentages can sometimes suit your financial circumstances. In fact, some financial planners have argued that 60 30 10 is a more reasonable plan in a world with higher housing costs than in the past.[3]

Overall, adjusting the rule’s percentages can sometimes be necessary, but it’s also important to recognise when straying from the guidelines is fueling poor financial habits. 50 50 0, for instance, could risk undermining your long-term financial health.

Is the 50 30 20 rule a good solution to achieve long-term financial goals?

The 50 30 20 rule is a good framework to help you achieve long-term financial goals, but it’s not a full-scale solution on its own. Allocating 20% of your after-tax income to savings and investment is a good rule of thumb for most individuals. It’s not appropriate for every case, however.

Imagine you’re a high earner following the 50 30 20 rule. In this situation, budgeting 80% of your income on things like housing, food, and entertainment may be far too much. Blindly following this rule could lead to lifestyle creep and insufficient savings in the event that you lose your source of income.

Alternatively, consider an individual in a low-paying job trying to follow the 50 30 20 rule for long-term financial health. Despite rigorous budgeting, 20% of this person’s income may simply not be enough to secure a robust retirement or build up a meaningful emergency fund.

In this case, investing time and money in training programs or education that unlock a higher salary may be more fruitful to long-term financial goals.

Disclaimer

The information contained above does not constitute financial product advice nor a recommendation to invest in any of the securities listed. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. When you invest, your capital is at risk. You should consider your own investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may receive back less than your original investment. As always, do your own research and consider seeking appropriate financial advice before investing.

Any advice provided by Stake is of general nature only and does not take into account your specific circumstances. Trading and volume data from the Stake investing platform is for reference purposes only, the investment choices of others may not be appropriate for your needs and is not a reliable indicator of performance.

$3 brokerage fee only applies to trades up to $30k in value (USD for Wall St trades and AUD for ASX trades). Please refer to hellostake.com/pricing for other fees that are applicable.

Article sources

[1] BCG - Consumer Spending Report Australia

[2] ABS - Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product