What is a stock warrant and how do they work?

Warrants are a unique type of derivative asset with the potential for enhanced returns due to embedded leverage. Read on to find out how these instruments work and the different kinds of warrants on the market today.

Stock warrants explained

Stock warrants are a type of derivative contract that give investors the right, but not the obligation, to trade an underlying asset at a pre-determined price in the future.

‘Call warrants’ grant the holder the right to purchase the underlying asset.

While ‘put warrants’ allow the holder to sell.

Warrants are closely related to options, another type of derivative. Both warrants and options give investors the right to trade an underlying asset and typically contain high embedded leverage. In addition, both warrants and options tend to come with a fixed expiration date.

Unlike options, warrant terms are set by the issuer, not standardised by an exchange. This can lead to far greater customisation and diversity in warrants. Investors cannot ‘write’ warrants the way they can write options, resulting in different trading strategies.

Broadly speaking, there are two forms of warrants: covered and uncovered.

A company issues uncovered warrants directly, allowing holders to buy the company’s own stock. In contrast, banks or other financial institutions issue covered warrants, typically on underlying assets like equities, commodities, or currencies.

How do warrants work?

The mechanics of a warrant can vary greatly depending on the asset’s specific terms.

Even within a category like covered warrants, there is a diverse array of instruments, including instalments, MINIs, and Turbos. Some of the attributes that will determine how a warrant works include:

- Coverage: Since companies issue new equity shares when converting uncovered warrants, these assets have unique dilution risks. In contrast, covered warrants do not create new underlying assets when converted.

- Expiration Date: Warrants typically come with an expiration date, at which point the asset ceases to exist. There also exist ‘open-ended’ warrants, however, which do not expire.

- Warrant Style: Warrants come in two exercise styles: European and American. European warrants can only be exercised on the expiration date, while American warrants can be exercised any time prior to expiration. This distinction has nothing to do with geography – both styles are issued all over the world.

- Strike Price: The strike reflects the pre-determined price at which a warrant holder can transact, either buying (call) or selling (put) the underlying asset at that price.

- Premium: This is the expense that an investor needs to pay to purchase a warrant upfront. Some warrants, like those issued by a company to employees, come with no explicit premium.

- Detachability: Some warrants are issued alongside their underlying securities. If this is the case, the warrants may either be ‘detachable,’ meaning they are able to be sold separately, or ‘undetachable,’ in which case both must be sold as one unit.

Why do stock warrants get issued?

Just as stock warrants vary widely in terms of their structure, these assets are also issued to accomplish a diverse range of goals.

For example, companies frequently issue uncovered equity warrants to compensate key stakeholders.

Giving long-term European warrants to employees as a bonus, for instance, can reward workers while also incentivising them to stick with the company into the future. A company may also sell warrants directly to investors to raise capital.

Banks, meanwhile, typically issue covered warrants to satisfy investor demand. For instance, many covered warrants offer leveraged exposure to an underlying asset without the risk of a margin call. In some cases, banks may sell over-the-counter warrants to institutional investors to offer customised exposure to certain asset classes.

Example of a stock warrant

To understand how a stock warrant might work in practice, we can walk through an example of a European uncovered call warrant:

Company ABC issues a warrant on its own stock with a strike price of $110 and one year to expiration. The company’s stock currently trades at $100 per share.

ABC sells these warrants to investors for $4 per warrant. This figure reflects the upfront premium that investors have to pay. The company raises $4 million by selling 1 million warrants.

The company takes this $4 million and uses it to help fund a new factory to fuel growth.

After one year, the company’s growth initiatives are going well, and the stock is trading at $120 per share.

Since the share price exceeds the strike price, the investors choose to convert their warrants. The company creates 1 million new shares to sell to the investors at a price of $110, raising an additional $110 million.

If the investors want to hold onto their stock, they can. Alternatively, they could immediately sell their shares into the market for a profit of $10 per share. After accounting for the premium cost, the investors netted a $6 million gain on a $4 million upfront investment, resulting in a 150% return.

In this example, investors got a compelling return. If the company’s stock price tanked, however, the warrants would have expired worthless, with the investors losing all their capital.

Issuing 1 million new shares could result in existing shareholders being diluted.

Types of warrants

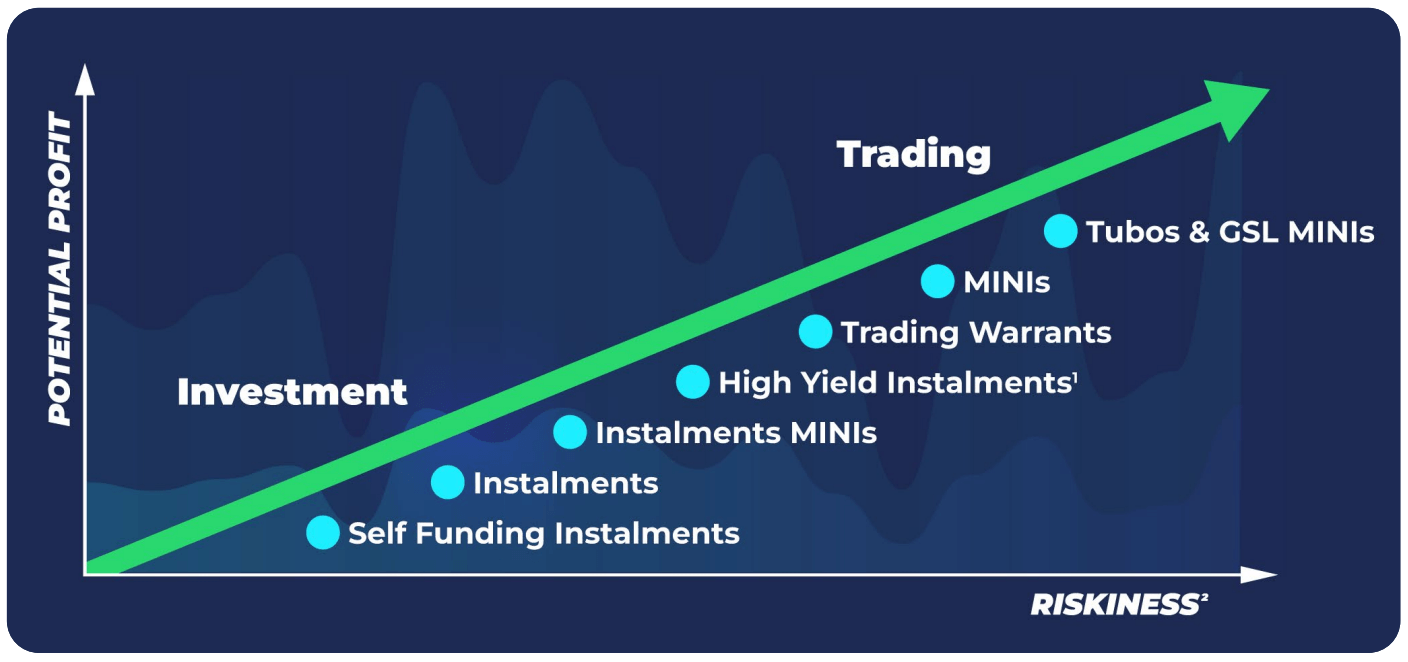

In Australia, there are several different types of exchange-traded warrants available, each with unique risk and reward characteristics. These uncovered warrants are all issued directly by a financial institution and generally fall into one of two groups.[1]

The first group is ‘investment warrants,’ which tend to be more suitable for buy-and-hold investors. The most popular type of investment warrants are instalments, which require investors to make an initial upfront payment and then feature a final, optional payment at expiration. Instalments can help investors access leverage on underlying assets without facing the risk of margin calls.

The other group of warrants are ‘trading warrants.’ These are typically cash-settled instruments that operate with a greater degree of leverage and are mostly designed for day trading purposes. Some trading warrants have unique features, such as open-ended MINIs and barrier Turbo warrants.

Warrants ticker symbols

Many warrants, especially those issued directly by companies, are over-the-counter instruments without a ticker symbol. Listed warrants, however, do come with a unique identifying ticker symbol.

In Australia, listed warrants trade with a six-code ticker.[2]

This ticker is composed of the following elements:

- The first three characters identify the underlying asset. For equity-linked warrants, this is typically the same three letters as the underlying stock.

- The fourth character identifies the type of warrant. Instalments, for instance, come with an I or J, while MINIs have a K, L, M, or Q.

- The fifth character identifies the issuer. CitiWarrants, for example, has an O code.

- The sixth and final character identifies a particular warrant in a series: A – O = Call / Long Warrant P – Z = Put / Short Warrant.

In some circumstances warrants can be shown with a five-code ticker as seen in the example below.

How to buy stock warrants

In Australia, stock warrants are listed on two different exchanges: ASX and Cboe Australia (formerly Chi-X Australia). While the ASX remains the country’s main warrant market, with 2,900 available warrants, Cboe has been making strides to catch up in recent years.[3]

There are two ways to purchase a warrant, regardless of which exchange the instrument is listed on. Investors can either purchase warrants in the primary market by subscribing directly from the issuer or purchase warrants in the secondary market post-issuance.

Buying warrants in the secondary market works much like purchasing stocks.

Note that not all brokers offer warrant trading, even if they list other ASX instruments. Warrants are a specialised type of asset, so you will need to find a broker that supports trading them.

What happens when my warrant is exercised or reaches maturity?

As a warrant reaches maturity, investors must decide whether to exercise their trading rights in the underlying asset.

For a call warrant, exercising is only advantageous if the underlying asset’s market price exceeds the strike price (and vice versa for a put warrant). If the warrant is American-style, investors may also prefer to exercise their position before expiry.

Some warrants are physically settled, meaning investors will need to actually buy or sell the underlying asset when exercising their conversion rights. Other warrants are cash-settled, meaning that conversion only requires money to change hands, rather than shares. This is more common in trading-style warrants.

What’s the difference between stock warrants and stock options?

Stock warrants | Stock options |

Issued by a bank (covered) or company (uncovered) | Written by an investor |

Can have an expiration date or be open-ended | Always have an expiration date |

Typically longer-dated, multi-year expiration dates | Typically shorter expiration dates in the weeks or months |

Customised terms set by an issuer | Standardised terms set by an exchange |

Typically many listed types | Typically just a few listed types (Calls & Puts) |

Are warrants a good investment?

Whether warrants are a good investment depends on your risk tolerance and investment goals. Warrants can potentially be a valuable tool to access increased diversification and higher leverage without needing to worry about margin calls. They can allow investors to gain exposure to a diverse range of underlying markets that they might not otherwise have access to.

With that said, the diversity of warrants on the market means that these instruments cater to a vast range of needs. A trading warrant may not be suitable for a buy-and-hold investor, for instance.

Ultimately, it’s important to closely study a prospective warrant to ensure you understand its terms and whether the asset aligns with your objectives.

Disclaimer

The information contained above does not constitute financial product advice nor a recommendation to invest in any of the securities listed. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. When you invest, your capital is at risk. You should consider your own investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs. The value of your investments can go down as well as up and you may receive back less than your original investment. As always, do your own research and consider seeking appropriate financial advice before investing.

Any advice provided by Stake is of general nature only and does not take into account your specific circumstances. Trading and volume data from the Stake investing platform is for reference purposes only, the investment choices of others may not be appropriate for your needs and is not a reliable indicator of performance.

$3 brokerage fee only applies to trades up to $30k in value (USD for Wall St trades and AUD for ASX trades). Please refer to hellostake.com/pricing for other fees that are applicable.

Article sources

[1] Cboe Australia - Investing in Warrants